China’s rising trade surplus is once again causing unease in the United States and Europe. But the real casualties from this new “China Shock” will not be in the West. They will be in the developing world, where hundreds of millions of people still depend on manufacturing for jobs and upward mobility. China’s trade dominance not only threatens growth across the Global South; it also undermines China’s own claim to global leadership.

Influential work by David Autor and his co-authors documented how the first China Shock, from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, wiped out manufacturing jobs and communities across the US. Yet much of that adjustment reflected deeper, long-term forces: technological progress and the steady reallocation of workers from factories to services – a shift that predated the China Shock, but was accelerated by it. As a result, advanced economies have largely vacated the low-skill sectors that China continues to dominate.

Today, China’s manufacturing trade surplus stands at roughly US$2 trillion, about US$1.4 trillion of which comes from low-skill goods. For the West, then, the new China Shock is narrower, concentrated in a few sectors such as electric vehicles and renewables, and in specific technologies where Chinese imports still account for about 1.5% of the West’s GDP.

The story is far more alarming for low- and middle-income countries ( LMICs ), which face a threat to the sectors where their comparative advantage lies – namely, low-skill manufacturing industries, which remain crucial for job creation and economic development. Accounting for almost 4% of LMICs’ combined GDP, the import shock from China represents a larger ( and growing ) share of their economies than imports of high-skill goods do in developed countries.

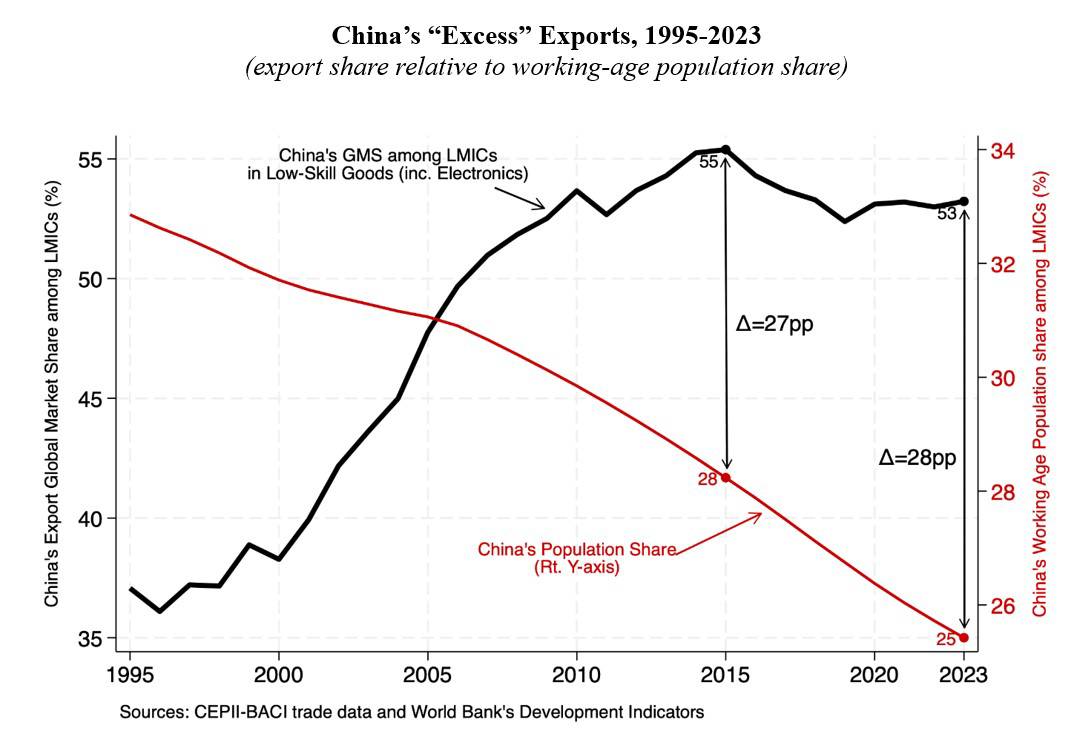

How serious is this threat? One benchmark is to compare China’s share of low-skill exports among LMICs to its share of the global workforce. China still accounts for more than half of global low-skill exports ( see chart ), and though its market share has declined slightly since peaking in 2015, the trend line should have been far steeper, given its shrinking labour force. The wedge between China’s export share and its labour force share – roughly 28 percentage points – suggests that China continues to occupy “excess” export space that could otherwise support tens of millions of manufacturing jobs in poorer economies.

What makes this persistence even more striking is that China’s manufacturing wages are now far higher than those in LMICs – and still increasing. For example, in apparel, the canonical labour-intensive sector, the annual wage in China averages around US$10,000, which is roughly five times higher than in Bangladesh and four times higher than in India.

Even with such wage differentials, China’s export strength might be less troubling if it stemmed purely from productivity gains and automation. In that case, one would still have to question China’s hegemonic legitimacy, because true hegemons accommodate rather than crowd out others, but it would not necessarily be unfair. Mounting evidence suggests that this is not the case, though. Instead, China shows signs of significant policy distortions. Industrial subsidies, undervalued exchange rates, and persistent excess capacity are all tilting the playing field in its favour. China’s continued dominance reflects not just efficiency, but deliberate policy choices that prevent poorer countries from climbing the development ladder.

History underscores how unfair China’s strategy is. Charles Kindleberger famously argued that hegemons provide global public goods, such as financing during crises, resources for long-term development, and support for open markets. When the US was the world’s economic hegemon after World War II, it created manufacturing and export space for others – first Japan, then the Asian Tigers, and eventually China itself. Its willingness to absorb imports and allow others to grow was an essential part of its global leadership. Yet today, as the Trump administration retreats from that role, China’s actions will determine whether it can credibly replace the US as a responsible provider of that critical global public good.

The pressure on LMICs is already evident in their growing trade actions against China. The recent unrest in Indonesia – a by-product of de-industrialization and exposure to Chinese competition – underscores what is at stake. To its credit, China has taken symbolic steps towards offering real leadership, including by voluntarily relinquishing its developing country status at the World Trade Organization and granting duty-free access to poorer countries.

But these gestures will ring hollow unless China genuinely vacates the global manufacturing space. If China truly aspires to global leadership, it must internalize a simple truth: hegemons gain legitimacy not by dominating others, especially the poor, but by enabling their rise. The new China Shock is not just about economic consequences. It is also a test of whether China can serve as a fair steward of global prosperity, or remain a formidable practitioner of beggar-thy-neighbour mercantilism.

Shoumitro Chatterjee is an assistant professor of international economics at Johns Hopkins University and a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; and Arvind Subramanian is a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former chief economic adviser to the Indian government.

Copyright: Project Syndicate