In recent years, the pattern of trade and investment in East Asia, and the shape of global value chains more broadly, have fundamentally changed, primarily due to the United States’ embrace of tariffs.

During his first presidency, Donald Trump imposed high tariffs on China, but largely left America’s other trading partners alone. This led East Asian firms, such as those in Japan and South Korea, to shift their supply chains away from China, toward Southeast Asia and Latin America, in addition to pursuing some reshoring.

Former US President Joe Biden largely maintained Trump’s tariffs on China and introduced some of his own. Moreover, in 2022, his administration pushed through legislation offering large subsidies and tax incentives for the production of green and high-tech goods, such as semiconductors and electric vehicles ( EVs ). This prompted East Asian firms to ramp up investment in the US, with South Korea surpassing Taiwan as America’s top foreign investor in 2023.

Trump’s return to the White House, which brought aggressive and unpredictable tariff hikes on US imports from most countries, sent this process into overdrive. With Southeast Asian countries generally facing significantly higher duties on US imports ( about 19% ) than Japan or South Korea ( 15% ), Japanese and South Korean firms have had a strong incentive to increase their US production. Hyundai Motors has already increased operations at its new factory in Georgia, while Samsung’s semiconductor foundry in Texas is under construction. Recently, facing the 50% tariffs, Posco has announced a joint venture with Hyundai Steel to build a steel factory in Louisiana. Since building and operating factories in the US requires importing large amounts of intermediate goods, total exports from these countries to the US have also increased. This has caused their trade surpluses to expand.

While this strategy might help these firms compete, at least for now, in a transformed global trade landscape, it risks hollowing out East Asian industry. After all, as firms increase production in the US, they must reduce domestic production. Toyota is already planning to sell its US-made vehicles in Japan in 2026 to “improve [bilateral] trade relations”.

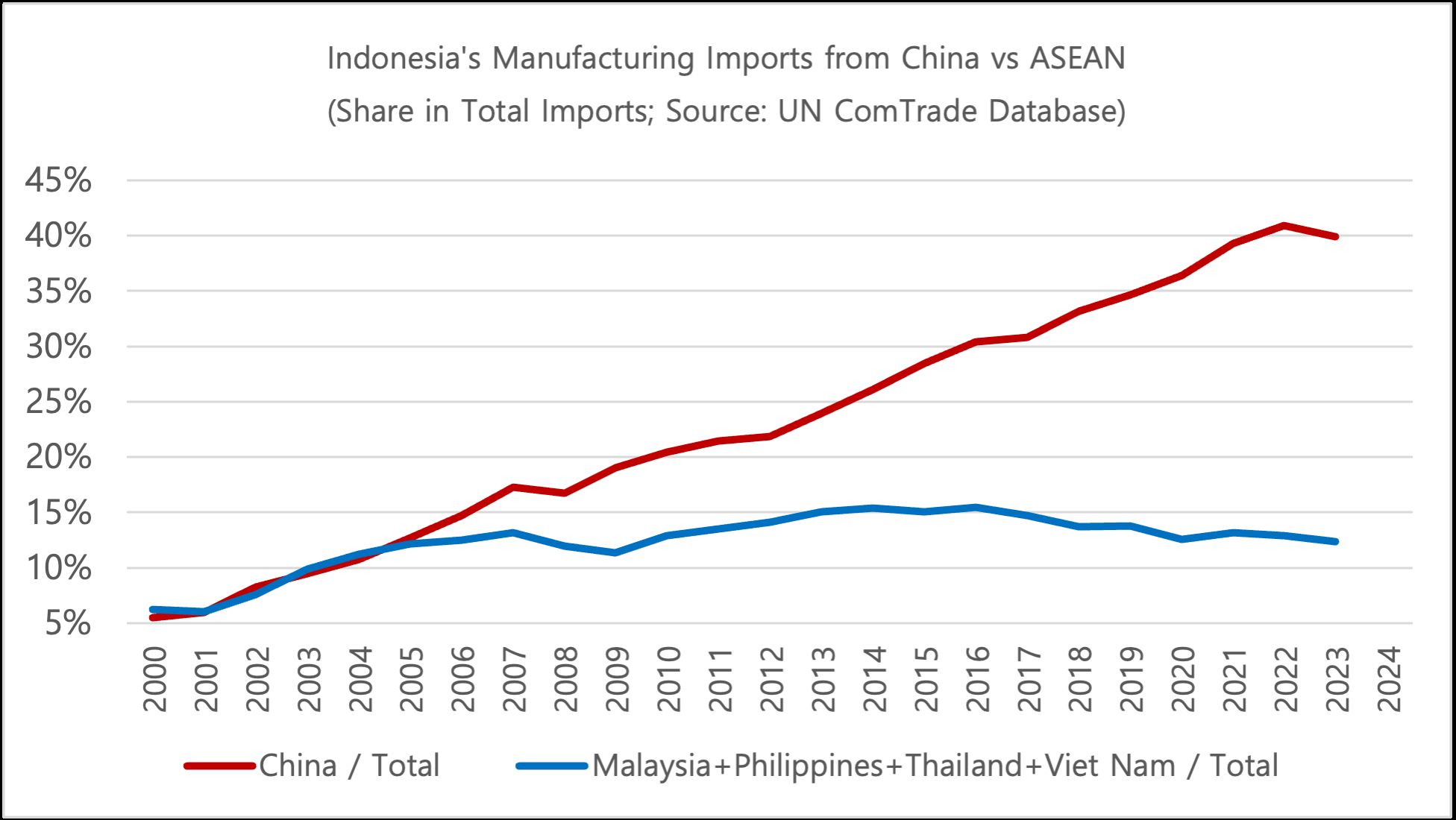

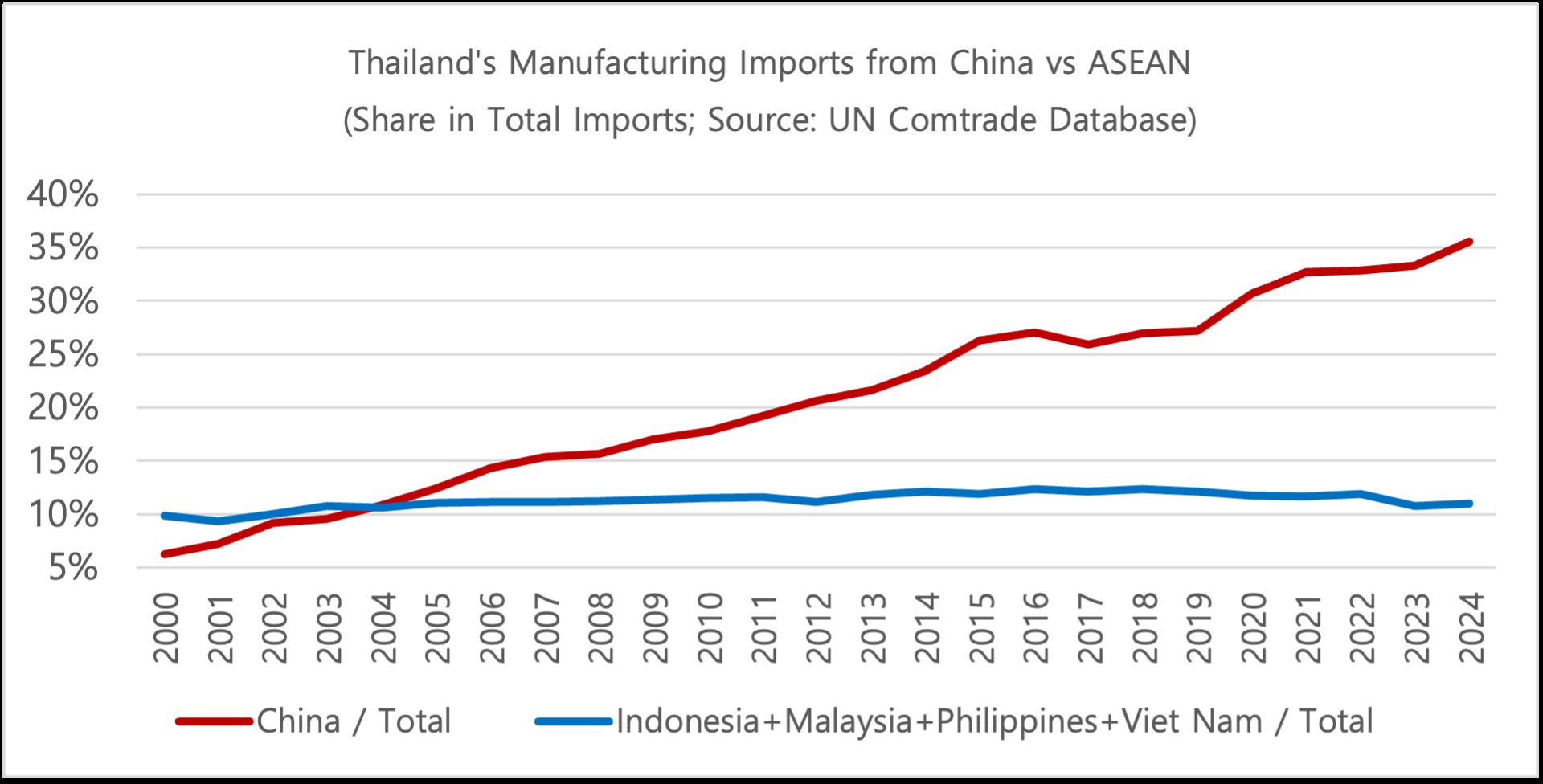

China’s actions are compounding the challenges for East Asian economies. Over the past two decades, China has been reshaping value chains, particularly in Asia. As Chart 1 shows, the country’s share of Indonesia’s manufacturing imports skyrocketed from about 10% in 2003 to more than 40% in 2022-23. Similarly, Chart 2 shows that China’s share of Thailand’s manufacturing imports rose from 10% in 2004 to 35% in 2024.

Chart 1

Chart 2

But China’s trade structure used to complement those of its Asian neighbors, whose domestic industry often got a boost from China’s rapid growth. As China has moved up the value chain, however, it has become increasingly competitive.

In Thailand, China has leveraged its EV prowess to seize market share from Japanese automakers operating in the country, often in collaboration with Thai firms. As Japanese companies like Subaru, Suzuki and Nissan scale back or end production in Thailand, demand for domestically produced parts and local workers will decline.

Furthermore, China has responded to high US tariffs by offloading cheap exports onto its neighbors. A flood of textiles from China is one reason why Sritex, one of Indonesia’s largest textile companies, declared bankruptcy in 2025. Similarly, an influx of cheap Chinese steel caused South Korean steel giant Posco’s profits to plummet by nearly 40% in 2024. South Korea’s government subsequently announced provisional anti-dumping duties on some Chinese steel imports, but they alone cannot safeguard the country’s steel industry, especially given high US tariffs on steel products.

Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea claim a very small share of China’s vast market. South Korea’s Samsung shuttered its last Chinese mobile phone factory in 2019, and now produces only three intermediate goods – semiconductors, EV batteries, and multilayer ceramic capacitors – in the country.

With the world’s two economic superpowers contributing to the hollowing out of East Asian industry, these economies’ prospects may seem bleak. But they do not have to be. Japan and South Korea, which used to compete directly in many areas, have developed more complementary economic structures in recent years, creating opportunities for mutually beneficial cooperation.

Though Japan has lost its supremacy in the final assembly of most goods ( except cars ), it produces an array of high-tech parts, equipment, and materials on which Korean firms depend to assemble their products, from semiconductors to consumer electronics. Moreover, South Korean “Big Tech” companies, such as Naver and Kakao, have expanded their presence in Japan, which lacks such firms.

Such exchanges could open the way for renewed discussions on a bilateral free-trade agreement. South Korea’s primary rationale for resisting such an agreement – fear that its persistent trade deficit with Japan would increase – is much less compelling than it used to be: the deficit has shrunk from nearly 40% of the total bilateral trade volume in 2010 to roughly 20% today.

Another option would be for South Korea to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which currently includes Japan, as well as Australia, Canada, Malaysia, Mexico, the United Kingdom and Vietnam. As a member of the CPTPP, South Korea would avoid the high tariffs that Mexico – South Korea’s largest trading partner in Latin America – recently announced it will impose on South Korean goods and those of other Asian countries, including China.

The global economy looks very different today than it did a decade ago, and East Asian countries must adapt. Only by deepening engagement with one another, and with other reliable partners, can these countries safeguard the industries on which their economies depend.

Keun Lee is a professor of economics at Seoul National University and a former vice-chair of the National Economic Advisory Council for the President of South Korea.

Copyright: Project Syndicate